For institutional investors the SDGs are a pragmatic guide to risk and opportunity. They don’t just help to future-proof capital allocations, they offer a huge boost to achieving the United Nation’s sustainability goals.

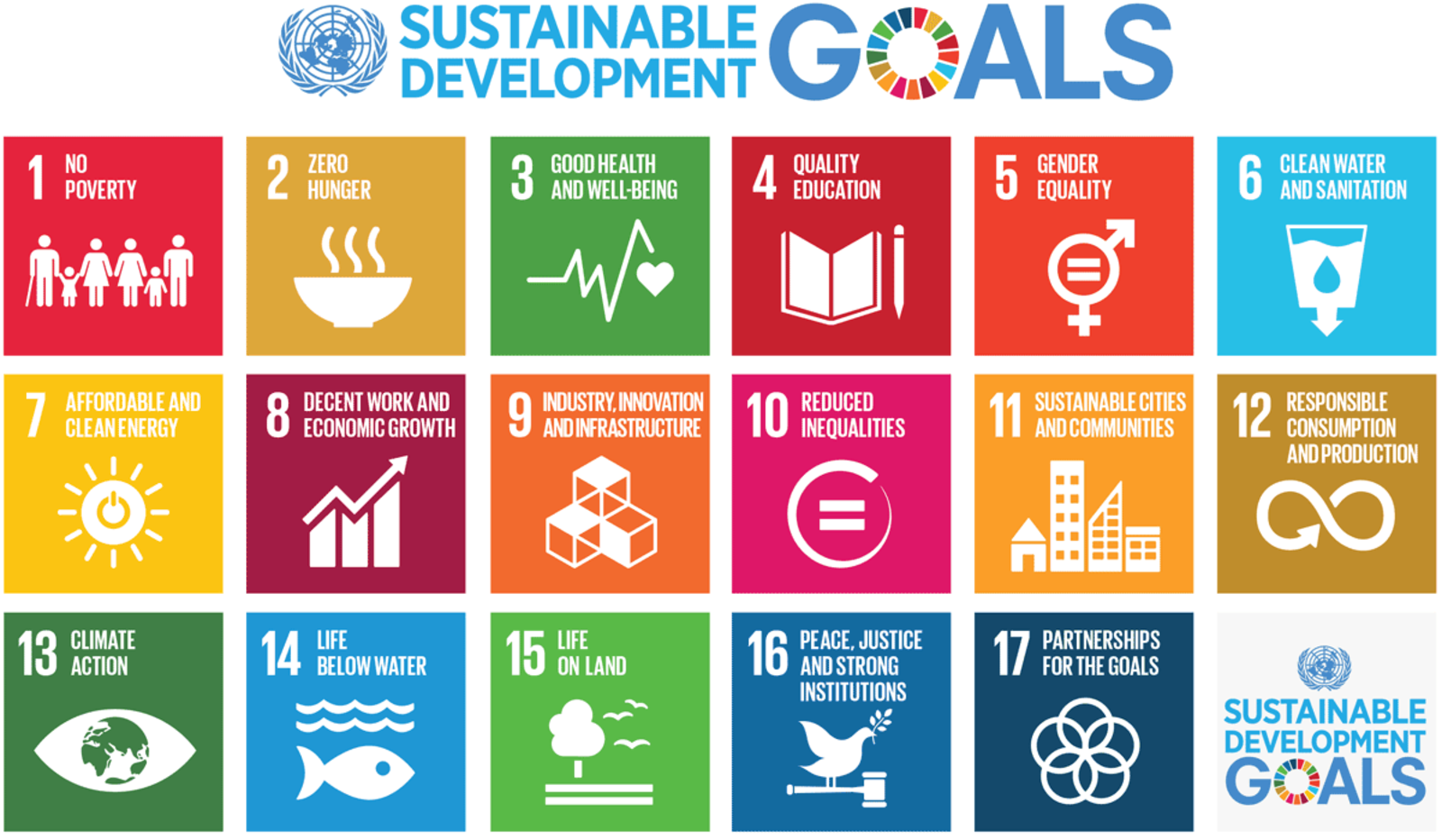

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are ambitious; launched in 2015 by the United Nations, they represent a global consensus on the most pressing social and environmental challenges facing our world.

There was early support from the usual suspects; government bodies, aid agencies and philanthropists. But as geopolitical strife and environmental catastrophe loom large, the world’s biggest investment managers are getting on-board as they recognise the immense benefits of driving their portfolios towards sustainability.

The 17 goals encompass the big issues; poverty, climate change, gender inequality and economic growth. And while the sentiment for action is strong, the cost of achieving the goals is eye-watering—UNCTAD (The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) estimates that it’ll cost up to $US7 trillion, that’s trillion, with a ‘T’.

The private sector was always going to have to play a central role, and there’s renewed enthusiasm as some of the world’s biggest money managers adopt the SDGs as a framework of risk & opportunity.

It’s recognition that a healthier and more stable world is a more prosperous one, and decisions made by money managers today will shape the potential for financial returns in the future.

I had the opportunity to work closely with the goals at the UN Global Compact last year, and I discovered a burgeoning field that aligns my finance experience with my post-graduate research work in international relations and human rights.

Sustainability is just long-term thinking

Responsible Investing and ESG integration have become standard approaches to portfolio management. For investment managers with long-term mandates it’s no longer a question of making ethical judgements, it’s now the pragmatic choice for risk management.

The SDGs offer a common language to define impact. For investment managers whose interests span the entire globe (universal owners) they represent a broad consensus, which is vital for investors wanting standardised frameworks and benchmarks, but also for asset owners wanting to compare managers.

Recent work by some of the world’s biggest pools of funds is forging indelible links between the sustainability goals and investment decisions.

Dutch-based pension fund managers PGGM and APG (managing in excess of $700 billion) have developed sophisticated methodologies that identify investment opportunities across 13 of the 17 goals.

They’ve titled them Sustainable Development Investments (SDIs) that, in their words, “bridge the gap between the UN’s targets and tangible investment opportunities.”

From investing $30 billion in SDIs in 2015, the funds have committed to this rising to $68 billion by 2020.

These big players in the Netherlands and Scandinavia have long been pioneers, but Aussie outfits like Cbus have also voiced strong support.

“While it was governments that signed up to the goals, actually achieving them is a shared responsibility for the business and finance sectors. Pension funds are coming together globally to develop a coherent set of scalable investment opportunities that can direct long-term capital towards achieving these goals.” Alexandra West explains, head of portfolio strategy and innovation at Cbus.

The SDG Investment Case

“The SDGs offer the greatest economic opportunity of a lifetime”. CEO of Unilever, Paul Polman, says in a new report from the UN PRI and PWC that offers enthusiastic support for the benefits of investing in line with the SDGs.

The UN PRI, (UN Principles for Responsible Investment) was never as flashy and colourful as the SDGs, but that image is changing.

The PRI is a network of investors who are working together to better align investing with the interests of society. Their mission was always somewhat hidden behind a mask of finance-speak, but with the launch of a ten year plan, the PRI Blue Print, they’re speaking-up and they’re making their agenda clear.

“Our challenge is to focus ever more deeply on what it truly means to be a responsible investor – and to then embed that so fundamentally and comprehensively in how all investors work that responsible investment as a standalone concept melts away.”

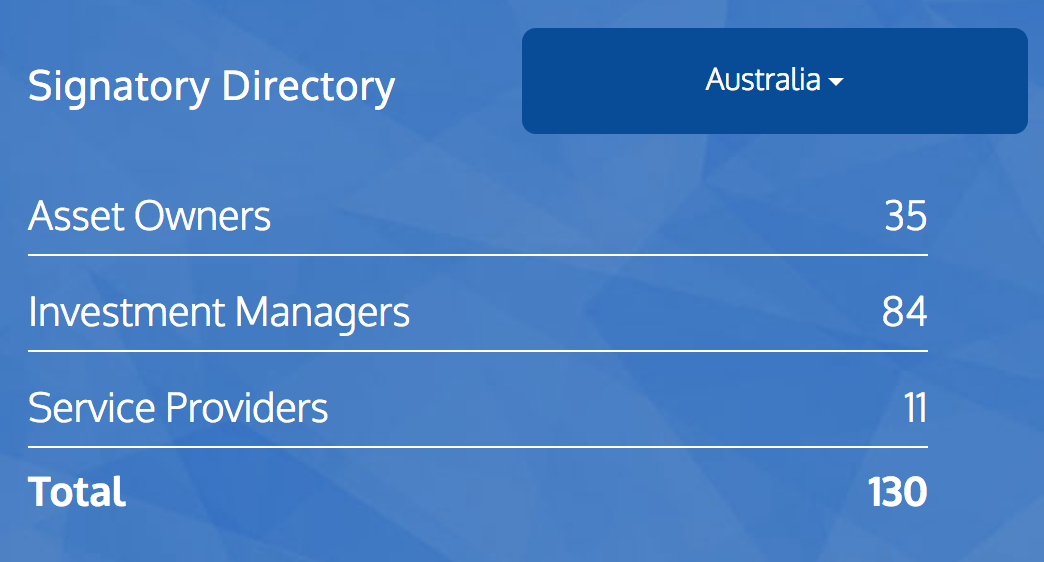

The UN PRI has 1,853 member organisations. Australia is well represented with 130 companies having signed up.

The report is called The SDG Investment Case and it steers clear of hyperbole to lay out a thorough argument for why institutional investors should integrate the SDGs into their thinking.

It takes to task the well-worn argument that an ESG focus may not be compatible with a fund’s fiduciary duty of maximising returns for members. Instead, it refreshes the investment perspective to focus on the sustainability goals as a framework of impending risk, as well as investment opportunities.

“The globally agreed SDGs are an articulation of the world’s most pressing environmental, social and economic issues and as such act as a definitive list of the material ESG factors that should be taken into account as part of an investor’s fiduciary duty.”

Sustainability to drive economic growth

From a macro perspective the report breaks down risks in terms of the exposure universal owners have to broad-based economic and social failure. It states unequivocally that the sources of growth that have driven returns over past decades are not sustainable, and that they can’t be relied on for future returns. They’ve resulted in environmental and social degradation and our economic model will need to shift.

“The active ownership model gives more weight than traditional portfolio management to inter-generational concerns and to the sustainability of the economy as factors affecting future risk-adjusted returns.”

There are risks but there are also opportunities. Economic growth is a strong driver of stock market returns, so if universal owners can contribute to economic growth they’ll be rewarded through their equity exposures. SDG 8 specifically targets “decent work and economic growth”, and as the other goals are achieved the social and environmental gains will further fuel growth.

The report cites the following research:

The BDSC says Incorporating SDGs into growth strategies could unlock opportunities worth $US12 trillion a year by 2030. (Business and Sustainable Development Commission)

Achieving gender parity would add between $US12 – 28 trillion to global growth by 2025. According to the McKinsey Global Institute.

A selection of 19 of the 169 SDG targets could deliver $US15 of benefit for every dollar spent, says the Copenhagen Consensus.

Don’t be left behind

Negative externalities are where the rubber hits the road for the tension between environmental protection and economic growth. This report argues that there are a number of key risk factors which might force companies to include environmental costs of production in their accounts.

I note the report uses the word ‘might’. Problems like pollution have long been the textbook example of a negative externality; it’s a cost of production that’s not included in the price of a product, but instead the cost is borne by society.

It’s highly likely that governments will ramp-up regulatory efforts in a bid to achieve the SDGs by 2030, in fact we’re already seeing it. And even if governments don’t lead the way, consumer preferences are already rewarding companies that operate ethically and as good corporate citizens.

The SDGs are a framework and a common language. This is vital when reporting efforts made, but also when engaging directly with companies to try and influence change.

Go long on the SDGs

Think of the SDGs as a lens through which to view investment decisions. Thematic investing is already widespread, and there are many opportunities to invest by focussing on a particular goal.

“If investors believe that providing solutions to sustainability challenges offers attractive investment opportunities, they can implement investment strategies that explicitly target SDG themes and sectors. In many cases, investors are implicitly taking these factors into account already, but not articulating it: the SDGs give a common language with which to shape and articulate such an investment strategy.”

Financial product innovation is going a long way to support these ambitions. An example is a collaboration between the World Bank and BNP Paribas to produce the worlds’ first SDG linked Bond. It raised €163 million from French and Italian investors and funds will be used support a range of development projects. Returns are pegged to Solactive’s Sustainable Development Goals World Index; which is made up of 50 companies with solid ESG credentials.

Closer to home Westpac has included SDGs 5 & 10 (reduced inequality) in their forward strategy. The bank aims to increase financial literacy and access to finance in the Pacific Islands. The region is a close neighbour to Australia as well as being one of our largest aid recipients. It’s a good example of how attempts to open up a new market can also be tied to achieving a major social and economic goal.

The low-hanging fruit

For investors that have already taken stock of the ESG credentials of their portfolios, a cross-referencing with the SDGs could offer low-hanging fruit. The SDGs are the result of a rare global consensus, and as the private sector is increasingly getting on board it is a language that everyone understands. Understanding whether any of your current investments are contributing to a particular set of the SDGs is a good place to start.

I’ll leave the final words to the eloquence of journalist David Bank from Impact Alpha;

“Pension funds were not interested in values-aligned investing when it was driven by aspirational, wishful thinking or, even worse, do-gooder advocacy.

They went from laggards to leaders when they assessed their portfolios against their long-term obligations, most obviously to pay out pensions to retirees decades in the future. There are few asset owners that don’t agree that between physical, policy and market changes, global warming will affect the investment landscape over the next 20 years. Likewise social instability driven by extreme income inequality will erode the value of institutional assets over time.

That makes sustainability selfish and unsustainability a major risk factor.”