Impact investing is no longer a seedling, it’s grown and matured and now there are fresh shoots springing up all over the world. But these communities all thrive in different types of soil and face different conditions.

The Global Impact Investor Network’s (GIIN) has released its annual survey for 2018, which gives us a global perspective, while the Responsible Investment Association Australasia (RIAA) paints a more local picture of impact investing.

Both groups are working to support this infant industry, but there are some surprising differences in how they see the market.

Comparing the two helps us visualise the size and growth of the impact investing space, but it also shows us the differences that come from the conditions in which you grow.

Impact investing is more than just investing

Before we dive into the numbers I want to quote one of the introductory lines from RIAA’s Benchmarking Impact report. Here Simon O’Connor, RIAA CEO, distils the power of impact investing, and the unlikely influence it wields.

“When compared to the broader financial market, some may argue that the size of impact investments remains small and as a result, inconsequential. However, this would be to miss the much greater market influence of impact investing, which goes to the very nature of how investing is considered.

This emerging industry has some deep lessons for finance – highlighting that all of our investments have an impact, whether positive, negative or neutral, whether intentional or not – and that the trillions of dollars flowing around capital markets today are shaping the Australia of tomorrow.”

Landing deals and achieving scale is important, but impact investing is really about a cultural shift in how ‘investing’ fits into our society.

Growth is good; but not at the cost of sustainability, clean oceans and efficient energy.

The market is growing, fast.

GIIN’s global numbers

It’s difficult to put a number on the size of the global impact investment market, but GIIN received responses from 229 organisations, and in total they manage $US228 billion. This number is broadly seen as a floor to the market.

In 2017 this group invested $US35 billion in 11,136 deals. They plan to increase their investments by 8 per cent in 2018.

(Data from the UN PRI values the total market at $US1.3 trillion)

Local growth

In Australia, the RIAA surveyed 24 organisations that manage a total of $5.8 billion at the end of 2017.

This represents growth of 105 per cent annually since 2010, and 143 per cent in the last 12 months!

This represents growth of 105 per cent annually since 2010, and 143 per cent in the last 12 months!

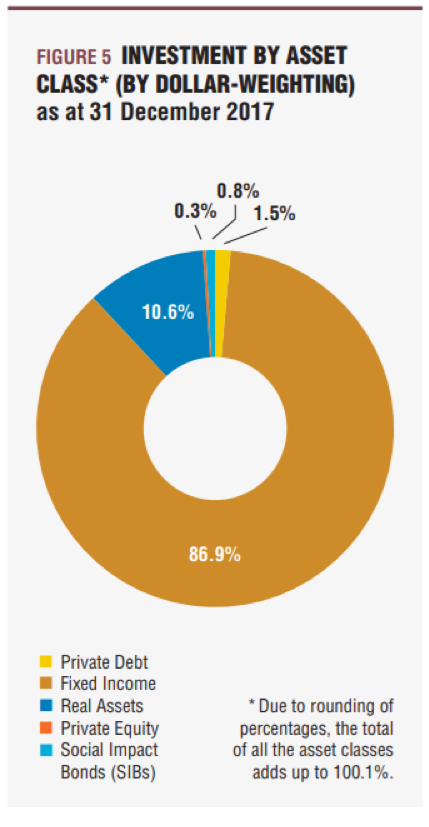

Notably this growth is mainly driven by green bonds, which account for 84 per cent ($4.9 billion) of the data set.

(See pie chart, courtesy of RIAA)

Excluding green bonds, the market value is $822 million, here property and infrastructure make up the largest proportion at 74 per cent.

The average for individual investment sizes is a material $9.4 million.

The GIIN recognises public equity funds, RIAA doesn’t

Green bonds were the biggest contributor to Aussie numbers, but the GIIN reports that it was ‘listed equity impact funds’ that recorded the greatest global growth, in their report. These are funds investing in companies that are listed on public stock markets.

It’s significant because these are relatively large, mature companies, and there are questions around how much influence (how much impact) a single shareholder can have.

I dug deep on the issue when I spoke to Ted Franks from WHEB, read here.

But most importantly, the RIAA had a different take. It was very clear that it did not include listed equity impact funds in its reporting.

“This study does not include any of the emerging public equities funds being labelled as impact funds. These products are excluded based either on unclear or insufficient intentionality or measurement of social/environmental outcomes, however, this area is evolving rapidly.”

The RIAA report goes on to say that progress is being made, they highlight the work of WHEB in producing an impact report, and they suggest listed equity impact funds will be included in the future.

The GIIN clearly sees the benefit of these investors supporting the work of listed companies that are doing good. And as long as the impact measurement frameworks are rigorous, and the companies are held to account, I tend to agree. But it’s a high bar to meet.

This category offers great potential for the industry to achieve scale, but it mustn’t come at the cost of true impact.

Paul Brest is a Stanford academic who’s well-regarded in the space, he has strong views on the issue which you can read here (paywall).

Emerging market investing is on the rise

Another key divergence between the GIIN’s global numbers, and RIAA’s snapshot of Australia, is in emerging market investing. While the GIIN sees an almost 50/50 split in developed vs emerging market investing, the Aussie impact investors captured in the report don’t deploy funds offshore at all.

The GIIN forecasts strong interest in emerging markets, with South East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa both being targets for a 44 per cent boost in investment. And among the 81 respondents who have responded over five years, they plan to grow allocations in Oceania by 45 per cent.

The RIAA mentions two organisations who have major offshore impact targets; these are Leapfrog Investments and Patamar Capital. This pair are achieving strong returns through targeting underserved, low-income markets. But they weren’t included in the final figures as they are domiciled offshore.

Blended Finance

The GIIN report offered some useful insights on blended finance, but it’s clear these strategies still have some work to do in simplification and ease of use.

“Blended finance is a strategy that combines capital with different levels of risk in order to catalyze risk-adjusted, market-rate-seeking capital into impact investments.

Seventy-five percent of respondents have either participated in a blended finance deal or plan to do so. A higher proportion of Below-Market Investors have participated in blended finance investments compared to Market-Rate Investors; the same holds true for Private Debt compared to Private Equity Investors.

Most respondents agree that blended finance de-risks transactions for investors (83%) and can be used to ‘attract funding for large-scale, high impact investments’ (66%) or ‘bring together expertise from different organizations and players’ (52%). Thirty-five percent of respondents also believe that blended finance can improve impact performance.

Most commonly, as cited by 45% of respondents not participating in blended finance deals, is that such deals do not fit their investment models.”

The RIAA’s Australian perspective didn’t have much to say on blended finance. But there is some positive work coming from DFAT in the form of the Emerging Market Impact Investment Fund (EMIIF).

Details are thin on the ground but it’s a $40 million fund that aims to attract and de-risk private capital to support growth in neighbouring countries.

Impact measurement is still highly fragmented

Impact measurement is a core issue for the growth of impact investing. While financial accounting is well established, measuring impact is far less mature.

GIIN says 66% of respondents are using proprietary metrics that are not aligned to external methodologies. This seems like a big number, and it begs the question of how their deals can be compared within the market.

IRIS is the most established global framework and 59 per cent of respondents say they use it. So there must be some cross-over.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer a valuable set of goals and targets that are universal. And 75 per cent of investors are tracking their performance to the SDGs.

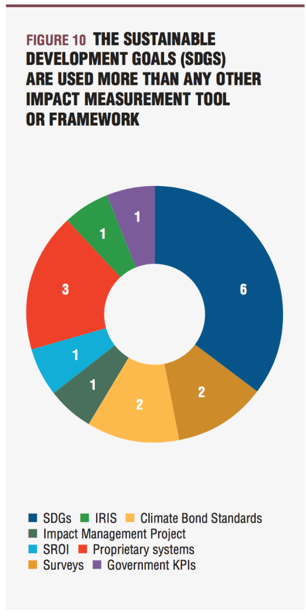

The RIAA shows that impact measurement is equally as fragmented here in Australia:

- 35 per cent of respondents have engaged with the SDGs.

- Two are using IRIS metrics.

- Two have adopted the Climate Bond Standards.

- One has engaged with the Impact Management Project

- One respondent employs Social Return on Investment as a measurement technique

Also, five of the 17 respondents draw on ‘other’ measurement frameworks that encompass proprietary measurement systems, surveys and government KPIs.

The pie chart shows which of the SDGs are being targeted by Australian impact investors. The spread is quite narrow, which is due mainly to the lack of Australian investors with any offshore impact holdings.

Which SDGs are receiving greater investment:

- Goal 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities;

- Goal 9 Innovation, Industry and Infrastructure; and

- Goal 13 Climate Action

Which SDGs are not receiving Investment:

- Goal 1 No Poverty,

- Goal 2 Zero Hunger,

- Goal 5 Gender Equality,

- Goal 6 Clean Water and Sanitation,

- Goal 16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

The RIAA report is thorough on this topic, explaining the lack of universal metrics and impact metrics that look only at outputs, not broad-based community ‘impact.

“While the raw numbers reported have increased in many categories over the 2016 figures, it is unclear how these counts relate to meaningful change in the lives of beneficiaries and the communities in which they live.”

This is the space where impact investing can have the most… impact. But it requires thinking beyond risk & return trade-offs.

It requires thinking deeply about an investment long before negotiations start. It’s about spending time with beneficiaries to find out what they need, rather than simply offering what you’ve got.

By first establishing the positive community outcome that’s being sought, investors can better deploy capital and create truly sustainable enterprises that build communities, build better lives, stronger economies and profits.

Opportunities, risks and challenges

GIIN’s wide data-set and global mix of investors offers us a valuable overview of the market. Here they’ve broken down respondent’s’ views on what’s going well and what’s likely to cause problems.

Opportunities

- Availability of ‘professionals with relevant skill sets’ (90%),

- The ‘sophistication of impact measurement practice’ (88%),

- Access to ‘high quality investment opportunities’ (86%)

- And, ‘research and data’ (85%)

Risks

- They see ‘business model execution and management risk’ as severe (29%),

- Significant ‘country and currency risks’ (22%)

- As well as the oft-cited ‘liquidity and exit risk’ (22%)

Challenges:

Respondents allocating capital to different, specific regions generally agreed (more than 60%) that a lack of appropriate capital is a top challenge facing the industry. Perceived challenges otherwise varied widely by region of investment:

- A lack of ‘appropriate capital across the risk/return spectrum,’

- ‘suitable exit options,’

- And a ‘common understanding of definition and segmentation of impact investing market.’

It is notable that 80 per cent of respondents agreed that “greater transparency from impact investors on their impact strategy and results” would help maintain their impact focus.

Transparency and accountability are vital in all financial markets. But impact investors must go a step further as they attempt to quantify very subjective, very human factors. They must ensure that investors and beneficiaries alike are honest and clearly aligned about what’s trying to be achieved.