The thing about impact investments is the best of them look like regular investments.

This article first appeared on ANZ Bluenotes.

Take fund manager Leapfrog Investments. In late 2017 the company sold a major stake in emerging market mobile insurance provider BIMA to insurer Allianz for $A96 million.

It’s a healthy return but more importantly, in the four years Leapfrog was invested in BIMA it helped sell 30 million insurance policies across 14 countries. BIMA is now the largest life insurance provider in Cambodia and doubled the insurance penetration per capita of both Ghana and Bangladesh.

Here in the West we may take our insurance policies for granted but in developing countries access to affordable insurance options is a game-changer which can greatly improve quality of life.

“Insurance provides a crucial safety net and springboard to people working to rise in the middle class,” Leapfrog founder and CEO Andy Kuper says.

“It enables everyone from farmers to taxi drivers and shopkeepers to take worthwhile risks; this might include starting and expanding a business, or sending their children to school rather than to work.”

They recognised serving this immense market would have major social impacts, while also offering returns to its investors. This is impact investing—a blend of philanthropy, finance, sustainability and development aid—and it’s growing.

More choice

Investors expect financial data but calls are growing louder for impact data to be made available as well.

Leapfrog’s investors were given insights into the social impact of financial inclusion. This is as important to them as the profit margin earned by their innovative fintech solutions.

This trend is also operating more broadly. Whether it’s the everyday Australian wanting to know how their superannuation fund is being invested or the world’s biggest fund manager BlackRock pooling its votes to force petroleum giant ExxonMobile to declare its climate change risk – there’s a growing force around the globe demanding answers.

All investments have impact, some are good and some are bad. Impact investing is at the vanguard of a trend which values a company’s impact as much as its financial results.

Wearing the label of an impact investment doesn’t come lightly.

Impact investment definition

If you choose to buy free-range eggs over the cage option, you’re making an ethical choice about where your food comes from.

There are clear definitions around the terminology to ensure brands which wear the free-range label are adhering to a certain standard.

For an investment to wear the impact investing label it must deliver both intentional and measurable returns – at least according to GIIN, a global industry association helping cement the industry.

“The growing impact investment market provides capital to address the world’s most pressing challenges in sectors such as sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, conservation, microfinance, and affordable and accessible basic services including housing, healthcare, and education.” GIIN explains on its site.

The Leapfrog example represents the traditional impact investment structure: it’s a fund manager holding major stakes in private companies where they exert direct influence over board decisions and day-to-day operations. It drives profit maximisation while ensuring positive social impacts are never compromised.

Private companies like BIMA, operating in under-appreciated markets, are rare and the opportunity for investments like these are in high demand. This has led the industry to expand the options available, in search of scale.

We are now seeing impact funds sprout-up around the world, owning shares in publicly listed companies – like the WHEB Sustainable Impact Fund from Pengana – rather than having direct control of private companies.

These investment funds tend to focus on a particular cause, whether it be fighting climate change or promoting women’s empowerment.

One fund might include shares in a global mix of companies which are leaders in renewable energy, or another might be filtered by those with strong representation of women on corporate boards.

The companies which fit the requirements hope to be rewarded by an increase in demand for their shares, as well as the valuable kudos and social capital of being recognised as an impact leader.

As with the free-range egg example, the tag of impact investment makes an investment increasingly attractive. However, where free-range eggs tend to cost more, an impact investment doesn’t necessarily have a higher cost.

Most impact investors expect their investments to have returns in-line with mainstream markets – and that’s happening.

Strong returns

Investors no longer have to take a hit to their returns in order to support companies which are leading the way on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors.

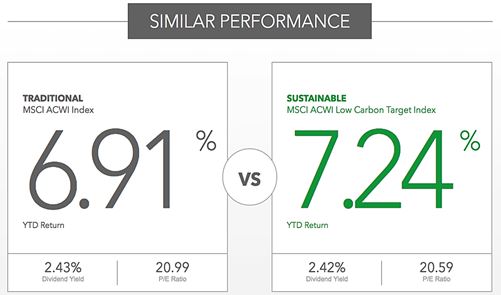

There’s plenty of research highlighting the superior performance of companies focussed on sustainability.

This may come as a surprise – and it has the old-guard of the finance industry sitting up and taking notice of what used to be the niche focus of ‘greenies’ and ‘tree-huggers’.

Source: Blackrock

A more sober view comes from private markets where Cambridge Associates established an impact benchmark comprised of only private equity, debt and venture capital.

It was then compared to a mainstream index with similar asset exposure. The ‘private impact benchmark’ came close, it returned 6.29 per cent over 15 years, but it was slightly behind the 7.84 per cent earned by the broader index.

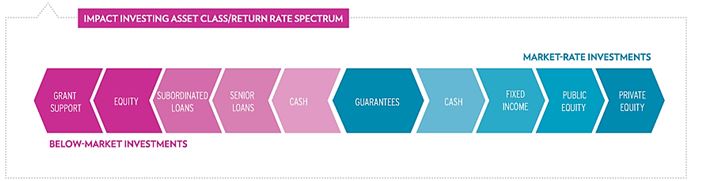

Of course impact investments are not all the same. They each focus on a particular ‘intentional’ outcome and financial returns are offered on a spectrum.

Asset-class/return spectrum. Source: GIIN

A charitable foundation might have a particular interest in supporting a business which provides affordable meals for the homeless.

The long-term aim of the business is to grow and become profitable but in the early years the foundation might be happy to receive a lower financial return to ensure the social impact return is maintained.

This is in contrast to our Leapfrog example which would be far to the right in the private equity category where financial returns are equal to, or higher than, those available in mainstream markets.

Who are the players?

Superannuation funds

While there are plenty of super-funds which offer their members ‘sustainable’ investment options, only a few have made the leap into impact investing.

HESTA (Health Employees Superannuation Trust Australia) made a strong commitment with its $A30 million Social Impact Investment Trust.

The fund is managed by Social Ventures Australia (SVA) and will be focussed on the health and community services sector. So far it has made headline investments in affordable housing and a dementia village.

Christian Super may be a small player in terms of funds under management but it’s a big hitter in its commitment to Impact Investing.

Chief Research Officer for the fund’s investment company Simba Marekera says 10 per cent of their portfolio fits under a strict impact investing definition, while the remainder is all screened in-line with their ethical and environmental standards.

Governments

Growth in social impact bonds has shown even Governments are embracing market-based solutions to solve big social problems. While their structure may be difficult to get your head around, the community benefits are clear.

The Newpin Bond was Australia’s first social impact bond with the aim of reducing the number of children in foster care. Private capital was raised with the promise of healthy returns if certain social indicators were met. The $7 million bond funded UnitingCare Burnside’s New Parent and Infant Network (Newpin).

It helps return foster children to their parents while also preventing at-risk children from entering the system.

Results are looking good: in 2017, 203 children were restored to their parents and in return the government paid investors a return of 13 per cent – a win-win situation.

It’s a trend building a lot of interest all over the world. In the US they call it ‘pay-for-success’ projects and the country’s Congress just gave the scheme a big funding boost.

Charitable Foundations

Foundations have long had the difficult task of balancing both the distribution of grants, as well as investing their benefactor’s funds.

Traditionally these two sides didn’t meet, and in some cases foundations have found themselves investing in companies in conflict with their core mission.

Impact investing is an opportunity for foundations to unite the two sides. This is the path the McKinnon Family Foundation has taken offering both grants and investments across climate change mitigation, renewable energy transition and poverty alleviation.

For McKinnon the decision between making a grant or an investment comes down to the nature of the project.

“Most of our grants are advocacy related, not service delivery or infrastructure, so they’re not suitable for investments,” Dr John McKinnon says.

“We choose to make an investment when a project produces revenue (such as a building purchase, infrastructure development such as renewable energy, or social enterprise development). We’d be reluctant to grant when a loan could be made with a reasonable prospect of repayment.”

Dr McKinnon has little doubt other foundations will embrace it.

“Growth has been strong, and yes, I do think that most (probably not all) will eventually adopt some form of impact investing,” he says.

“You ask yourself, why spend 5 per cent of your money doing good when 100 per cent is invested in doing “bad”? It’s a strong argument, and as the opportunities for impact investing grow the case will become more and more compelling.”

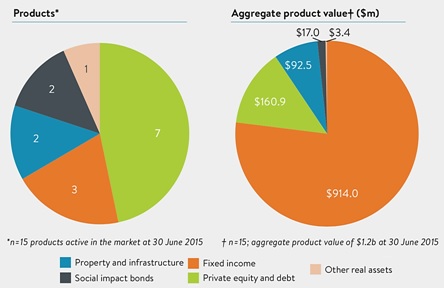

How big is the Impact Investing market?

Total value of impact investments by asset class

Source: impact investing Australia – Benchmarking Impact 2016

The semantic challenges of defining impact investing also make it difficult to estimate the size of the market. The GIIN suggests a floor for the global market of $US114 billion, which is the total assets under management (AUM) of 209 of the world’s leading impact investors.

Closer to home the RIAA suggests the Australian market sits at $A4.1 billion AUM in its Responsible Investing Benchmark Report.

This may seem modest but it’s growing, it’s up 10 per cent from 2015. The growth has come from a combination of government support, new pure-play fund managers and social impact bonds issues by community funds and the major banks.

The large bulk of Aussie impact capital is currently in the form of green bonds, such as those issued by banks like ANZ.

There’s also a lot of activity in the form of debt financing which comes in the form of loans to social enterprises to help build their businesses. These were supported by the three Social Enterprise Development and Investment Funds (SEDIF) built with the support of the Federal Government and its $A20 million cornerstone investment.

A savvy fintech deal

So is the Leapfrog deal an impact investment or a savvy fintech deal? Well, it’s both – and that’s what will define the future of impact investing.

The aim is to reach a time when the term ‘impact investing’ is no longer needed. A time when all investments will be expected to report on their impact, whether it be positive or negative.