You may remember the news headlines from 2008, “Childcare-centre giant ABC Learning collapses under a weight of debt”. But what many don’t realise is that when Michael Traill (and a syndicate of investors) won the bid for the assets they would in-turn define the power of impact investing in Australia.

The business would go on to become Goodstart Early Learning; it revived some 672 childcare centres but it also paid a 12 per cent return to its investors. Most miraculous of all was that it went down amid the ashes of the global financial crisis. Funds were tight, but it was the social mission at the heart of the project that set it apart.

Since then Impact Investing has gone mainstream. As the industry booms a flurry of financial products and investment vehicles are hitting the market.

With such proliferation, this amorphous term ‘Impact Investing’ is being stretched and pulled and it seems to mean a lot of different things to different people.

Amit Bouri, CEO and founder of non-profit organisation GIIN, has said that 2017 marks the ten-year anniversary of the term’s adoption. It was in 2007 that he attended a meeting, convened by the Rockefeller Foundation in Bellagio in Italy and this is where modern Impact Investing, the process of deploying capital for both social and financial returns, was born.

“Ten years into the creation of a formal impact investing industry, we are digging even deeper into the data and exploring the hard questions the survey surfaces about the market’s development.” Bouri says, in the GIIN’s 2017 Annual Impact Survey.

Now, in 2018, the market has grown and positive sentiment has grown with it.

GIIN’s 2018 Survey was authored by Research Director, Abhilash Mudaliar, he says “Fundamental norms governing the role and purpose of capital in society are changing, and impact investing is at the forefront driving this transformational shift.”

The 2018 survey collected responses from 229 of the world’s leading impact investors who control a combined $US228 billion of assets-under-management (AUM)—a figure that’s broadly recognised as a floor for the market. These investors reported a very healthy increase in AUM of 13 per cent per annum.

In an attempt to try and define key terms, and to get a gauge on the current state of impact investing in Australia, I reached out to those leading the way. I spoke to fund managers, asset owners and social entrepreneurs to get their perspectives on a concept that holds so much promise for addressing major global issues.

Read: Michael Traill: Update on Social Impact Taskforce

Impact investing definition

The GIIN offers a broadly accepted definition:

“Impact investments are investments made into companies, organisations, and funds with the intention to generate social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.”

It’s beautiful in its simplicity; thanks in no small part to the pioneers that have built the industry over past decades.

It goes on, “Impact investments can be made in both emerging and developed markets, and target a range of returns from below market to market rate, depending on investors’ strategic goals.”

This covers a lot of ground; investments must be intentional and their impact measurable, and returns can be above or below market levels.

This is an important point, returns from Impact Investments don’t necessarily have to be concessionary. In fact, the booming demand for these assets is being driven by their healthy returns. (Leapfrog is a great local example, by some reports its portfolio companies have grown revenue in excess of 40 per cent annually).

Investments that target impact will always operate on a spectrum of returns—concessionary investments sit at one end, think philanthropic grants or charitable donations. While non-concessionary investments sit at the other, they demand risk-adjusted, market-rate returns. In-between you have investors willing to concede returns at various levels; it might be a ‘catalytic’ investment to nurture an infant industry, or an ethical aim driven by a mission-specific benefactor.

So, that all seems clear enough, right?

I certainly had more questions:

- That all just sounds like ESG integration and Socially Responsible Investing (SRI)?

- How big is the Impact Investing market & what are the asset options?

- If there’s money to be made, why aren’t mainstream investors onto it?

- Can listed companies be included in an Impact Investment fund?

- Why now? What’s changed?

Impact investing vs ESG integration and SRI

In an ideal world we wouldn’t need to tag investments with “impact” or “ESG”, instead all businesses would be held accountable for their environmental and social impact. They would measure it and then it would be reported to their customers and to their investors—but we’re not quite there yet.

What we do have is a set of indicators and filters that help investors identify companies that operate with principles (and risk profiles) similar to their own, while avoiding those that don’t. These indicators start broad, before growing more narrow and more specific.

At the broadest level is Socially Responsible Investing (SRI). This represents investors who either include or avoid certain stocks, depending on a set of criteria. Their focus can cover everything from listed, multinational companies to small private equity opportunities. This is the negative and positive screening process that you might recognise being used by superannuation and pension funds to exclude industries like: firearms, tobacco and gambling. This approach first surfaced in the 1970’s and it stems largely from an ethical standpoint.

The next stage in narrowing the lens is ESG Integration. This is a recent evolution from the concept of SRI, and it’s much more than just a tightening of the positive and negative filters.

ESG refers to three factors that investors should consider in a company: Environment, Social and Governance.

ESG integration involves these three factors becoming key considerations in the core of the investment process. Assessing environmental, social and governance performance certainly helps weed out certain “sin stocks” in the same way as SRI. But it goes beyond making ethical judgement calls, instead, it’s a powerful indicator of risk and opportunity that can be applied to companies that may have already been pre-screened for profitability.

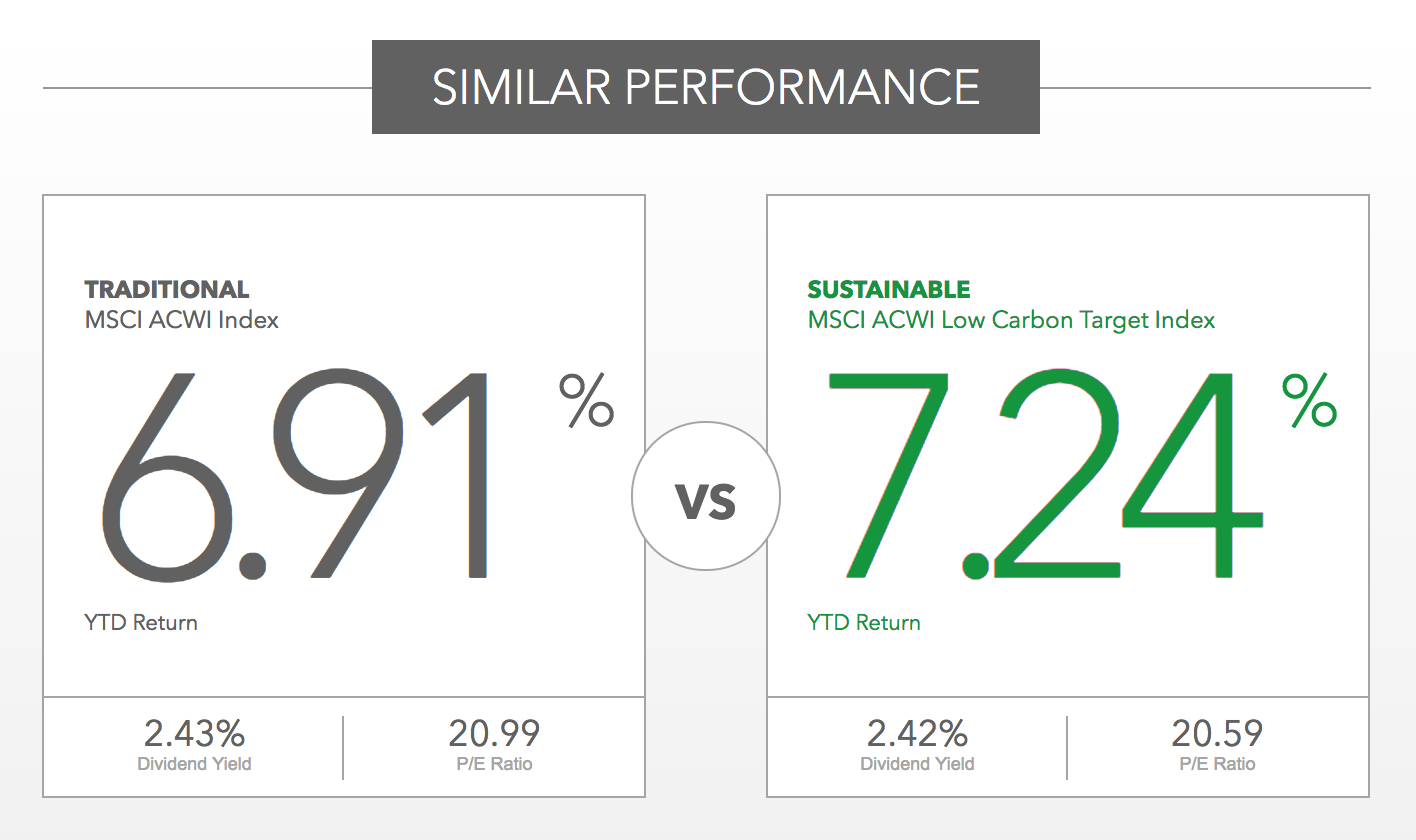

A key point to consider is that companies that perform well on ESG metrics haven’t necessarily had to sacrifice returns to get there. In fact, they can be more profitable. These companies tend to take a longer-term perspective on their operations and offer greater transparency; the results are hard to ignore. According to a Barron’s survey, funds with an ESG focus consistently outperform their non-ESG peers.

Even BlackRock, one of the world’s biggest money managers, has a sustainable investing division.

Broad adoption of ESG integration across institutional investing can be put down to its effectiveness as a risk metric, as much as the growing demand from asset owners for sustainable and ethical investment products.

The Responsible Investment Association of Australia’s 2017 Benchmark Report suggests, “nearly half (44 per cent) of Australia’s assets under management are now being invested through some form of responsible investment strategy”.

As the focus on ESG increases, its impacts are being felt. Very large and very powerful corporations are cleaning up their acts to impress both customers and investors.

ExxonMobil, for example, faced fierce pressure from a majority of investors (led by unprecedented pressure from BlackRock) regarding the way it reported its long-term exposure to climate risks. The oil giant conceded and will now report on the impact of global measures coming out of the Paris Agreement.

But what of the new breed of companies that don’t have a dirty past to clean-up, nor a polluting product at the core of their operations? What about companies that are focussed as much on making a positive impact as they are on making a profit?

This is where Impact Investing comes in.

Impact investments tend to target individual companies in specific sectors, and the large majority are in private markets. In dollar terms, compared with the previous categories, it’s small. But, as is suggested in the name, the impact is large.

These are companies and social enterprises that are working to solve problems that, in the past, were left to not-for-profits and government grants. There’s a range of models, here are some examples:

Pollinate Energy, has developed a low-cost solar light, and with the addition of an innovative business model, it is changing the lives of people in villages all over India.

The social enterprise Streat offers training and employment in the hospitality sector to at risk youth.

Hepburn Wind runs Australia’s first community-owned wind farm, just outside Melbourne.

And a brand most will recognise, Thank You. This social enterprise sells sustainably produced bathroom and food items, but, it gives 100 per cent of its profits to a range of charities.

These companies have dismissed the old rules of doing business. Instead, they’re focussed on selling something that has a positive impact. It’s a commercial model that ensures they can continue to do good long into the future; without worrying about when the grant funding will run out.

These are small private companies and, just like any other business, they need investors to help them grow. The difference here is that there is strong demand from investors who are looking for opportunities to earn a return AND, do good at the same time.

This rapid evolution has left some inconsistency in terminology. Simba Marekera, Chief Research Officer at Brightlight Group (a subsidiary of Christian Super), explained that some managers maintain a “broad” definition of the term impact investing; they use it to include negative and positive ESG screening and integration, active engagement as well as intentional & measurable impact investments. While a narrow definition restricts it to investments with intentional & measurable positive social & environment impact.

“If you take the broad definition, Christian Super’s portfolio is 100 per cent impact investing and if you take a narrow definition, Christian Super’s portfolio is 10 per cent impact investing. The 10 per cent allocation is all unlisted across equity, debt and hybrids.” Marekera says.

How big is the Impact Investing market & what are the asset options?

It’s not the size of your fund, it’s how you use it.

Impact Investing in Australia is estimated at $4.1billion (according to the RIAA Benchmark report) and a global survey of major managers puts a floor on the broader market at some $US114billion.

While the dollars may pale in comparison to mainstream funds (there’s $2trillion in Australian super funds alone), that’s not the point. The companies being targeted, and the fund managers that are helping them grow, are in the vanguard of a new form of capitalism, and they have impact at their core.

“These impact investments are directing capital to a range of areas from health and disability to conservation and the environment that have more traditionally been the province of grant funding. In the process, this market is supplementing the limited resources of governments, donor organisations and philanthropy with new private capital seeking public good.” According to Impact Investing Australia’s Benchmark Report 2016.

The report goes on to suggest that in 2015 the vast bulk of activity, in dollar terms, came from green bonds, representing some $914million. (It’s a limited data set but it offers a good indication of the spread across asset classes.)

In terms of volume of transactions, most activity is happening in the form of debt financing within the three Social Enterprise Development and Investment Funds (SEDIF). In 2015 these made up 82 per cent of deals, comprising an array of debt financing solutions to social enterprises and community organisations.

What is SEDIF? “SEDIF involved the Australian Government making a AUD 20 million cornerstone investment to seed three new investment funds to improve access to finance and support for Australia’s social enterprises to help them grow their business, and by doing so, increase the impact of their work in their communities. By establishing the SEDIF, the Government is also seeking to catalyse the development of the broader social impact investment market in Australia. The SEDIF funds are the first social investment funds of their kind in Australia.” OECD research explains.

The three seed funds were: Foresters Community Finance, SEFA and SVA. Government assistance has now ceased but these three private funds remain. They continue to work as central pillars of the Australian Impact Investing eco-system.

See the SEFA Annual Impact Report 2016 here, to get a feel for their mission and their focus on outcomes.

There are also organisations such as Giles Gunesekera’s Global Impact Initiative which is working with London-based World Wide Generation on a $US250m Affordable housing project in Mumbai. It involves building new housing and loans being directed towards capacity building for local entrepreneurs.

It’s an evolving space with a broad range of investment opportunities, but all are united by having measurable and intentional impact at their core. Plus, the bulk are offering returns in-line with mainstream markets.

If there’s money to be made, why aren’t mainstream investors onto it?

“You don’t need to take a haircut to join this club.”

One of the most hotly debated topics in the world of impact investing is the question of whether impact investors should expect to earn market-rate returns.

It’s a puzzle that I battled with as I began to learn about the sector. With such advanced financial markets I assumed that any investment earning market-rate returns, or above, would have been promptly exploited by mainstream investors. Wouldn’t these ‘impact investments’ just become plain old ‘investments’?

At the Impact Investing Summit 2017 in Sydney there were diverging views. Paul Steele from Benefit Capital was adamant that solid returns are to be expected:

“If you’re asking the question is it financial first or impact first, then you’ve missed the concept of impact investing.”

He added a useful analogy, “Impact investing is like a platypus. When you first see it you find it difficult to believe it’s real.”

This was in contrast to Don Shaffer from RSF Social Finance, he spoke at length about the importance of shifting profit expectations if we want to change the economic model, “I think we need to embrace more risk, lower returns & less liquidity. We need to question if historical rates of growth are sustainable?”

To get a theoretical perspective we can go back to an article from 2013, written by Paul Brest and Kelly Born, in the Stanford Social Innovation Review. It went deep to define terms, to explain the spectrum of concessionary returns and it also raised the question of additionality, “But if an impact investor is not willing to make a financial sacrifice, what can he contribute that the market wouldn’t do anyway?”

Consider the pharmaceutical industry, there’s plenty of money flooding into companies working to improve lives, but that’s arguably driven by profits alone. The impact exists, but it’s not intentional in the sense we’re exploring.

Brest & Born make a distinction between outputs and outcomes. “An output is the product or service produced by an enterprise; the (ultimate) outcome is the effect of the output in improving people’s lives.”

“So the impact investor must answer two questions: First, to what extent will the intended output occur? Second, to what extent will the output contribute to the intended outcome (where the counterfactual is that the outcome would have occurred in any event)?”

So, at the heart of it, we’re asking…

In what circumstances would there exist an enterprise (an investment opportunity) that has the potential to offer both high returns and measurable impact, but, which the broader market has not yet recognised?

One answer is that these are not long-established perfect markets. Instead they are often obscure private markets with some kind of ‘friction’. So, there are any number of reasons that a small, agile investor, looking at out of the way locations, and looking through a unique lens, might find a special opportunity that mainstream investors would not see.

Brest & Born suggest these ‘frictions’ include:

- Imperfect information

- Skepticism about achieving both financial returns and social impact

- Inflexible institutional practices

- Small deal size

- Limited exit strategies

- Governance problems

Their report was certainly influential, with some of the leading practitioners in the field weighing-in to debate in the comments. To some degree, the theory surrounding additionality has been resolved. As with carbon credits, it’s a matter of effective governance.

The report also raised the issue of listed markets, and whether investors can still have an ‘impact’ in this space. While Brest & Born made it clear they felt listed companies were beyond the scope of impact investing, the market has moved ahead.

Hungry for growth and scale, listed impact funds are using their capital to influence the world’s biggest companies.

How do public (listed) companies fit into impact investing?

So far we’ve recognised the tendency for Impact Investing companies to be small, privately held enterprises. This was how the industry began, and it makes sense; the owners and the board have direct control of strategy and operations to ensure the impact doesn’t give way to short-term profits.

The problem is that the market for these kinds of companies is limited.

Giles Gunesekera, explains, “There are experienced Impact Investors out there that feel the only way to translate a proper strategy is to take a share holding in a private, unlisted company, to get on the board and to exert influence from the inside, and that’s fine, that’s a great strategy. But the problem is it’s not very scaleable.”

Tapping into the investment/impact potential of public companies (those listed on a stock exchange) has huge potential to amplify the spirit of impact investing.

The obvious problem is that these companies have a world of capital available to them, they’re bought and sold at the click of a button, so how can investors hope to have an influence?

The key factor is related to the ESG issues discussed previously, but it remains focussed on the need for intentional and measurable impact.

A report from The Impact, a network for family offices, suggests three core investment strategies for investors building an impact portfolio with listed equities;

Screened portfolios:

- A fund can target companies that are “best-in-class” for a particular industry. While avoiding the worst performers.

Special-Interest portfolios:

- A fund can focus its capital on companies with particular operational or governance characteristics. Eg. solar power, gender equality or saving wild habitat.

Shareholder activism:

- They can organise and work together to vote for change.

- Made increasingly effective by the pooled voting power of proxy voters.

A UBS report from the 2017 Davos meeting is evidence that the biggest money managers are now taking the sector seriously, conceding that activism is vital; “Unless sustainable investors pressure companies openly and extract quantifiable concessions, it is hard to measure their impact on corporate behavior.” UBS plans to direct at least $US5 billion into Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) related investments over the next five years.

Closer to home Gunesekera says his team are building a range of funds with the SDGs as the focus; “First we establish the impact aims of our clients, then we work out how to map them to the SDGs. We currently have 12 different strategies, with some thematic cross-over. For example one strategy is around ‘women and girls’ and this targets four SDG themes.

We look for companies who have progressive policies and governance towards women in addition to organisations that empower and improve girls health, nutrition and education.”

These semantic issues about what classifies as Impact Investing have plagued the sector ever since its modern birth ten years ago, as Gunesekera says, “Impact investors fighting internally is not productive, we need to be doing more impact investing, not arguing about names and which approach is better.”

One concerted attempt to bridge these semantic gaps is the Impact Management Project. With the support of hundreds of fund managers, leading foundations and policy makers, it collects and publishes a consensus view on how practitioners, “talk about, measure and manage impact.”

Brian Trelstad, founding partner of Bridges Fund Management, is a strong proponent, “We are helping develop a common convention for impact management that will enable investors to articulate clearly and share their expectations around the outcomes they can expect from all of their investments, not just those in the impact field.” Trelstad says in an article for Investment Magazine.

Why now? What has changed?

You’d be hard pressed to find a finance magazine that hasn’t run a main feature on the current boom in impact investing. (See The Economist, Forbes and IPE) You get the distinct feeling something big is happening in the space.

But why now?

1) Capitalism is broken

The Global Financial Crisis was a wake-up call to the dangers of capital markets that focus on profits above-all-else. Greed and selfishness led to unprecedented risk taking, and when it all unravelled the pain spread well beyond those in the finance industry. A critical mass of investors is now looking for a new way. ESG integration and impact investing are the sharp end of a wedge that is shaking up the status-quo of financial models and modern portfolio theory.

2) Transparency

Social media and online data have made it harder than ever for companies and money managers to hide bad behaviour. Even the smallest retail investor can now assess their portfolio and align it to their values. The resurgence of activist-investors has shown that power in numbers can have dramatic impacts on even the biggest global companies.“This increased transparency means companies that are working to reduce negative externalities or solve critical societal issues are well known, celebrated and rewarded by both investors and consumers.” Simba Marekera explained.

3) Millennial mindset

In terms of impact investing the millennial cliché holds better than ever—they’re the most altruistic generation and they want to invest in-line with their personal values. Endless survey results point towards this demographic being socially aware and ready to deploy their money to do good. Here’s just a few:

Merrill Lynch via HBR: “Of all the generations alive today, millennials are the most willing to trade financial return for greater social impact.”

Morgan Stanley: “84% of millennials cite investing with a focus on ESG impact as a central goal.”

EY: “As millennials begin to engage with wealth and asset managers, they will continue to disrupt the industry due to their sizeable population, inheritable wealth and preference for digital channels of communication. Additionally, millennials more consistently select investments that align with their values than previous generations.”

World Economic Forum: “This does not imply that the next generation of investors will not seek market returns… the emerging generation of investors is also likely to seek achievement of social objectives in addition to financial returns.”

4) The SDGs

The United Nations’ fifteen year plan of action, the Sustainable Development Goals, were always going to be ambitious. But even the plan’s founders at the UN have been blown away by the energy with which the private sector have come on board to help achieve the goals. For pension funds and other long-term investors the SDGs represent a framework of risk and opportunity (see Pension funds & PRI driving the investment case for SDGs). In turn, this offers investors a tangible metric with which to gauge and compare companies on a global scale.

Conclusion

It’s been a rapid evolution. The concept of Impact Investing is pivoting and morphing before our eyes, and while defining such fluid terms remains difficult, the process is seeing unprecedented innovation in financial markets. This has real potential to shift economic models away from the blinkered risk-taking that led to the Global Financial Crisis. Is this the dawn of a new capitalist era?

Voices are growing louder, there is clear hunger for models of growth and development that take a long-term view of environmental protection and social inclusion. Facilitating these structures is a big job, and impact investing is leading the way. It’s setting an example for both investors and entrepreneurs about what it means to build a sustainable business. It’s progress.

Disclaimer:

This document is intended to be purely explanatory, it is not a source of investment advice.